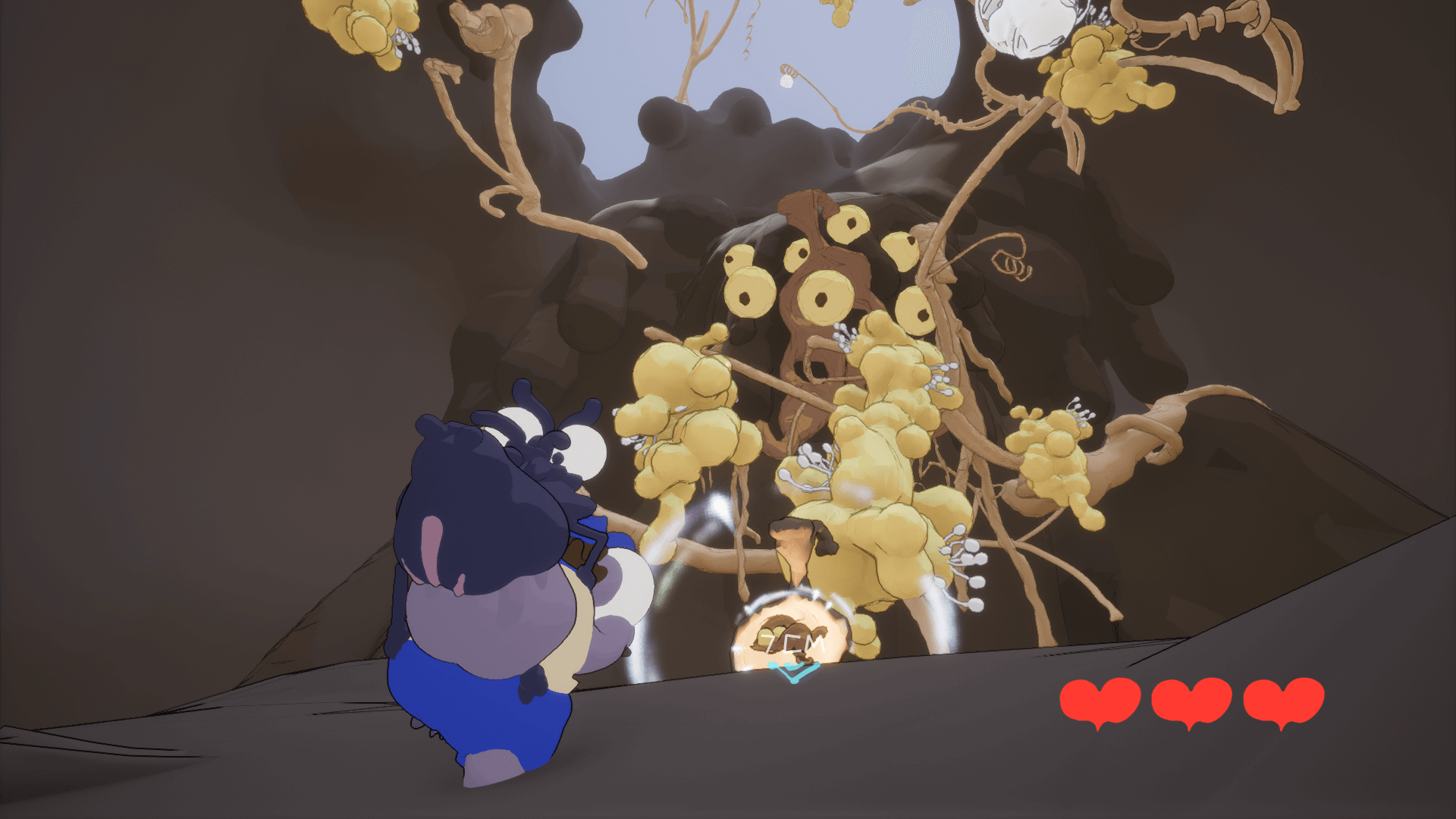

In an abandoned wetland, you take on the role of a tiny insect. Using spider silk to swing and hang nimbly, you wield a specially crafted weapon and rely on your agility to shoot down various hostile creatures lurking in the micro-ecosystem. Complemented by actions like jumping, grappling, swinging, and gliding, you navigate through the bizarre and complex micro-environment…

At first glance, Swing Swamp bears a resemblance to Splatoon. This is a small-scale 3D TPS (Third-Person Shooter) swing shooter that focuses on the rare “micro-world” theme, paired with a cute art style. Its developer, Insect_494, is indeed a Nintendo fan—elements like the game’s interactions, rhythm, and artistic aesthetics naturally carry a Nintendo-like vibe.

Insect_494 and his partner, Leiman (the programmer), used to be colleagues who co-developed VR games. Last year, the two made up their minds to create a game that followed their “hearts” and, through this project, first navigate the full process of launching an indie game.

After releasing a demo of this experimental game, they unexpectedly gained a group of active early players and caught the attention of several investment and incubation teams. However, after careful consideration, Insect_494 chose not to rush into securing funding.

How to enjoy the fun of game creation without being overwhelmed by real-life challenges? When faced with “temptations” like external investment, how to assess one’s own capabilities, and what choices are best for the game’s development at this stage?

Insect_494 believes that for fledgling indie developers, maintaining a steady pace in all aspects is perhaps the most crucial thing.

01 Translating Personal Interests and Aesthetics into the Game’s Worldview and Gameplay Mechanics

The initial inspiration for Swing Swamp came from the aesthetics and hobbies of Leiman (the programmer) and myself—it is a work fully driven by our interests.

The “micro-world” setting stems from my love for insects. For example, I incorporated the silk-spinning traits of bagworms and spiders into the game’s character design, and introduced the mechanics of swinging with spider silk and gliding on spider webs.

The addition of shooting gameplay, on the other hand, came from Leiman’s love for shooting games—this allowed him to leverage his strengths in designing shooting mechanics. Meanwhile, the diverse ecosystems and enemy scenarios in the micro-world complement the shooting gameplay well, enabling a rich variety of in-game mechanics.

In the end, we combined our respective aesthetic preferences and strengths to finalize the game’s core: a “micro-world” worldview paired with “swing shooting” mechanics.

Once the worldview was set, ideas for other settings naturally emerged. For instance, anyone who studies insects knows the impact of excessive herbicide use on micro-ecosystems; humans also often level large areas of vegetation for gardening or construction, causing the creatures that once lived there to disappear.

This dynamic involves the relationship between humans and other organisms, making it easy to create a sense of conflict. At the same time, it is a relatively uncommon theme for ordinary players—this uniqueness helps Swing Swamp stand out from the crowd.

For the “swing” gameplay, we also wanted to create differentiation, making the swinging feel more satisfying and the camera more expressive. To achieve this, our team made many attempts: we specifically studied the camera work in Spider-Man movies, repeatedly adjusted the position of grapple points during design, and explored how to let players experience that same sense of swinging.

Additionally, shooting in a micro-world obviously cannot rely on ordinary guns. In Swing Swamp, we finally chose peas (the plant) as the shooting weapon—somewhat like the Peashooter in Plants vs. Zombies—which also integrates perfectly with the game’s worldview.

We even designed a unique animation for loading peas one by one. While players might not notice such small details during battles, if they do, it could bring them the pleasant surprise of finding an easter egg. In the official release later, we will also focus on adding more plant-based weapons to enrich the player experience.

The demo of Swing Swamp was gradually developed through this kind of iteration and collaboration. Earlier this year, when we shared information about the game online, we caught the attention of Hou Xinyu, an indie musician.

After learning about Swing Swamp, she offered many creative ideas—including how matching new sound effects to certain scenes could enhance the experience. Leiman and I held an online meeting with her the same night and officially invited her to design original music and sound effects for the game.

Sound effects and music are crucial to a game; good music can deepen players’ immersion in the game’s unique atmosphere. However, most indie game developers cannot invest in music due to cost constraints.

In this regard, Swing Swamp was quite lucky. This kind of scenario is probably what many indie game developers aspire to: designing a game based on their own interests, attracting like-minded creators through the game, and working together to turn this dream into reality. Fortunately, the current indie game development environment is increasingly supportive of such collaborations.

02 Navigating the Launch Process Independently May Be More Meaningful for Start-Up Teams

We have always positioned Swing Swamp as a passion-driven, exploratory product. This positioning is also tied to our personal experiences.

Around 2017, Leiman and I worked at the same game company, serving as artist and programmer respectively. We co-developed a VR game together—though the project was small, we built a strong rapport through close collaboration. By 2021, I wanted to create something I truly loved, so I started trying to develop games on my own, and would occasionally ask Leiman for help.

This state continued until 2024. Both of us hit bottlenecks in the projects we were handling at the time. Coincidentally, we also came across the same video on Bilibili around that period: it told the story of a foreign developer who, after hitting a wall in his main project, participated in a Game Jam (game creation marathon) and quickly finished and launched a game in just one month.

We were both inspired by this story and wanted to attempt a fast-track iteration: navigating the entire process of indie game development and launch on our own. So we joined forces to develop Swing Swamp.

The early development of the game was almost entirely done online. Unlike large teams, which prioritize planning and documentation first, small teams pursue short, direct communication—this allowed the game to iterate very quickly. We would often propose an idea in the morning, start working on it right away, and by the afternoon or evening, we would review the results together once the prototype was ready.

Even some of our development processes were “unconventional.” When we worked on the VR project earlier, the team was small and the company provided limited resources, so I figured out a way to use a VR headset with built-in modeling software to assist in creation—and found it to be highly efficient. After completing 2D concept designs, I could quickly verify scene structures in VR space or check if the back of a character matched the original art, for example.

When developing Swing Swamp, I directly reused this experience, even using my old Oculus Rift at home. The assets generated in VR could be directly applied to the game, with no issues in terms of artistic quality or optimization.

I was never a senior 3D artist to begin with, so I’ve always taken a more unorthodox approach. Somehow, I found a more efficient method and stuck with it. As a creator, tools can be all kinds of things—you can experiment freely with them. The key is to have a genuine desire to create something.

Beyond the game development itself, everything else was a process of “crossing the river by feeling the stones”—including figuring out how to launch the game on Steam. For example, we didn’t know that each product only gets one chance to be featured in Steam Next Fest. We rushed to participate in the event before perfecting the demo, which wasted this valuable exposure opportunity.

Unexpectedly, after participating in Steam Next Fest, several major companies took notice of us. At one point, incubation teams from these companies reached out to us, and we even got to the stage of discussing development plans with contracts in hand.

In the end, however, since Swing Swamp is an exploratory product and our team has always maintained a relatively loose remote work structure, we were worried that external involvement would lead to high expectations from the other party—expectations we might not be able to meet. We didn’t want to hold them back, nor did we want to risk everyone getting stuck in an unpleasant development rhythm later on. After discussions, we reached a consensus with these companies: we would continue to explore independently for the time being.

Leiman and I both have years of industry experience, and our living costs are low. When we decided to become indie developers, we made up our minds to spend the next five or six years creating what we love. If things really don’t work out, we can still support ourselves by taking on outsourcing projects. The key is to think clearly in advance whether you can accept the potential costs.

03 Let External Feedback Fuel Progress—Without Disrupting Your Rhythm

Although we didn’t end up collaborating with major companies, their suggestions, along with feedback from players after the demo launch, brought us a lot of insights and reflections.

On one hand, the recognition and opportunities we received boosted our confidence and expectations for the game—we became more eager to polish it to a higher standard.

Increased confidence is inherently a good thing, but overly high expectations led to a brief loss of control in development. We wanted to add too many features, and the scale we aimed for far exceeded the team’s capabilities. This is a common pitfall for many indie game developers.

In particular, Swing Swamp uses a linear level design, which means adding new content always has a “ripple effect”: every new weapon or enemy introduces additional work across the board. When we mapped out the timeline, we were shocked by how large the game would become if we kept going at that pace.

A few months ago, the team had a serious discussion about controlling the game’s scale. We reflected on the fact that development shouldn’t spiral into an endless expansion. Fortunately, we hit the brakes in time—currently, the game’s scale is still manageable for our three-person team, and we can complete and launch it by October 2025 as planned.

Game creators, especially indie teams, can easily get caught up in the joy of creation. But if creation becomes purely about pleasing yourself, it’s easy to overlook player experience and development costs. In fact, once you step back from the excitement, you’ll realize that some features are overly personal—they add little to the game experience but create huge cost burdens for the team.

On the other hand, as we communicated more with the outside world, the game received a wide range of suggestions—filling the gap of not having professional game testers on the small team.

We iterated on the game multiple times based on this feedback. For example, an investor suggested adding escape sequences to the level design to increase excitement and reduce development pressure. While we didn’t fully adopt this idea, it still inspired us to make improvements to the game.

Another example: recently, we received two separate pieces of feedback pointing out that the visual effect of spider silk breaking in the game was underwhelming. We had never noticed this issue before, but after receiving the feedback, we immediately adjusted the design—increasing the “breaking force” and adding a character roll animation. This simple change made the scene much more vivid.

The biggest lesson from this experience is that developers must break out of the “isolated creation” mindset. While it’s sometimes necessary to immerse yourself in your own vision, players’ needs and experiences deserve respect. When you listen carefully and make improvements based on their feedback, you’ll also feel that your work is becoming more impactful—better able to bring joy to others.

Of course, we also faced dilemmas while incorporating feedback. Some experienced shooting game players insisted that a shooter should not have a UI indicator showing the number of remaining enemies. This debate went back and forth many times, leaving the team confused for a while.

After discussion, however, we still believed that the decision depends on the game’s style: some games are more hardcore, so their UI indicators are less prominent. Swing Swamp is a relaxed and fun game, so having some form of indicator is more in line with its tone.

That said, we can still optimize the indicator’s form based on the feedback—whether to use an NPC prompt, a UI percentage, or a progress bar. Each choice will shape the game’s unique vibe.

While listening to feedback, you must not get lost in players’ suggestions. As creators, you need to answer these questions: What should the game’s style and tone be? What solutions do players’ feedback offer? How should controversial elements be presented?

04 Indie Game Developers Need to Find Their “Creative Pillars”

Swing Swamp is scheduled to officially launch in October 2025. Although the final boss level is not yet fully built and connected, we have maintained a positive mindset. We also plan to add an endless mode after the official launch—so if players want more challenges after finishing the main game, they can dive into the endless mode for more fun.

While it may not match the quality of games specifically designed as roguelikes, we will adjust elements like weapon attack patterns in the endless mode to make the player experience more varied.

In fact, after releasing the demo, we already deeply felt the greatest achievement of a game developer: seeing players enjoy Swing Swamp. No matter how many late nights we spent polishing content, or whether we could eventually meet our expectations, it all felt worth it.

Looking back on my development journey, I hope all creators can find their own “pillars.”

For me, games, insects, and painting have all supported me in different ways during the development process. The more pillars a creator has, the easier it is to rely on other pillars when one is exhausted—allowing you to keep moving forward with energy.

Interview/Writing: Xia Qingyi, Huang Yuxiao

Follow the developer: X

Check the Steam Page: Steam

Based on the Chinese version interview: 《摇摆沼泽》:从VR游戏“退回”PC独游,野路子开发“昆虫版”斯普拉遁 | 创作手记